Safely handling a performance car isn’t about raw talent; it is about disciplined control, a deep understanding of physics, and calibrating your own senses to the vehicle’s reality.

- The laws of physics are non-negotiable: you must master energy management, as stopping power does not scale linearly with speed.

- Proactive safety means using the car’s superior capabilities for de-escalation, creating space and time rather than aggressively closing gaps.

- The greatest danger is often driver overconfidence, amplified by the car’s high grip levels which can mask a lack of genuine skill until it’s too late.

Recommendation: The first and most critical step is to shift your mindset from seeking speed to mastering control. Your goal is to develop a profound mechanical empathy for the car and its limitations.

You have the key in your hand. The low-slung bodywork gleams, promising an experience far beyond the mundane commute. This machine is a marvel of engineering, capable of feats of acceleration and grip that defy everyday physics. Yet, a quiet but persistent question emerges: are you capable of handling it? This gap between a high-performance car’s potential and a driver’s skill is the most dangerous place on the road. The excitement of ownership is often tempered by the dawning realization that the power at your command is immense, and your control over it is, for now, unproven.

Common advice often sounds simple: “be smooth with your inputs,” “look further down the road,” or the ever-present “take it to a track day.” While this guidance isn’t wrong, it’s critically incomplete. It tells you *what* to do, but not *why*. It offers rules without explaining the fundamental principles of physics and psychology that govern a car at its limit. Without understanding the *why*, this advice is just a collection of platitudes that will fail you when you need it most.

The true path to safely handling a performance car is not about chasing speed. It’s a journey into discipline and understanding. The secret lies in reframing your relationship with the vehicle. You must learn to think not in terms of speed, but in terms of energy management. You must develop a mechanical empathy for the tires, brakes, and suspension. This article is not about how to drive fast. It is a guide from an instructor’s perspective on how to be in complete control, turning the car’s mechanical limits from a source of fear into your most reliable safety tool.

This guide provides a structured framework for understanding the core principles you must master. We will dissect the physics, psychology, and practical realities of performance car ownership, giving you the mental models necessary for safe and confident driving on public roads. The following sections break down everything you need to know.

Summary: A Disciplined Framework for Performance Car Control

- Why Your Stopping Distance Quadruples When Speed Doubles?

- How to Anticipate Other Drivers’ Errors Before They Happen?

- RWD vs. FWD: Which Handling Characteristics Are Safer for Novices?

- The “Dunning-Kruger” Effect Behind Most Single-Car Accidents

- Problem & Solution: Adjusting Coilovers for Daily Comfort vs. Track Days

- Why Hybrids Lose Their Efficiency Advantage at Speeds Over 70 MPH?

- Why a 5-Star Rating Doesn’t Always Save You in a Collision With a Truck?

- What Are the Hidden Costs of Owning a Sport Coupé as a Daily Driver?

Why Your Stopping Distance Quadruples When Speed Doubles?

The first and most critical lesson in performance driving is not about the accelerator, but the brake pedal. The reason your stopping distance quadruples when you double your speed is due to a fundamental law of physics: kinetic energy equals half the mass times the velocity squared (E = ½mv²). This means the energy your brakes must dissipate as heat increases exponentially, not linearly, with speed. At 60 mph, your car carries four times the kinetic energy it had at 30 mph. Your brakes don’t stop the car; they perform the immense task of converting this violent energy into heat.

This principle is the cornerstone of energy management. A performance car’s massive brakes are not just for braking later; they are for managing this energy more effectively and consistently. However, they are still a finite resource. They can overheat and “fade,” drastically reducing their effectiveness. Understanding this relationship is a matter of survival. As research confirms, doubling the speed increases the braking distance by four times, a fact that many drivers fail to internalize until it is too late.

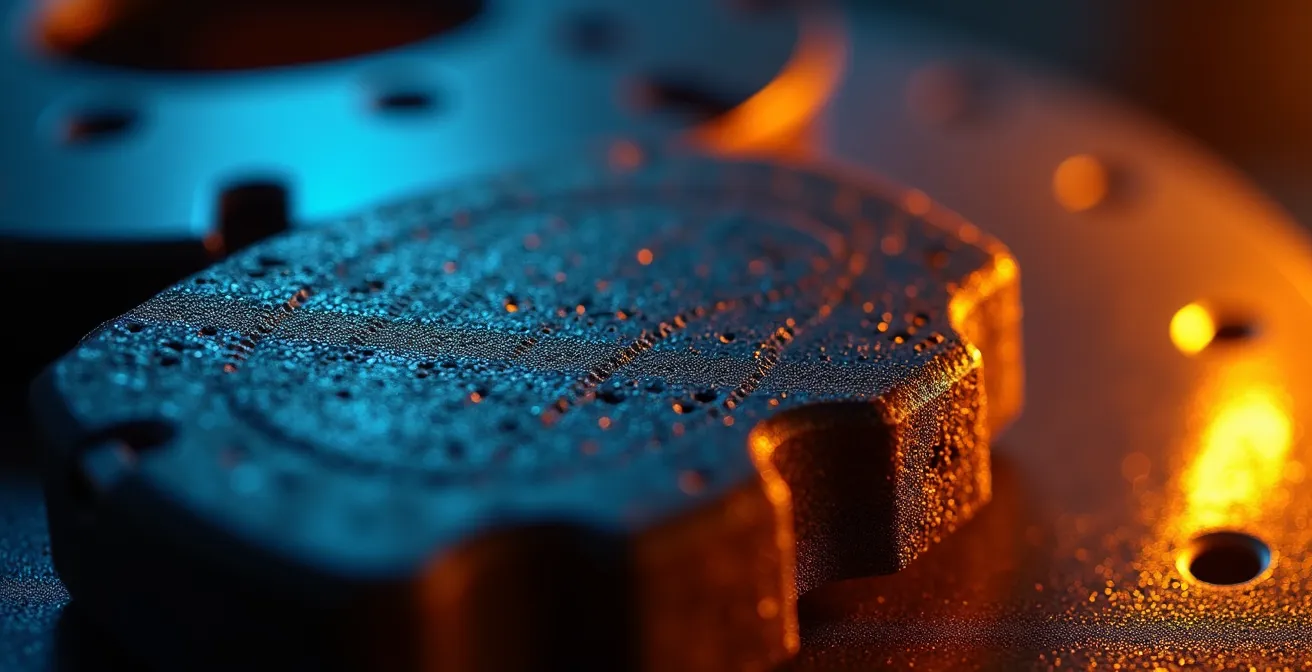

As this image of a carbon ceramic brake disc shows, the entire system is designed for one purpose: shedding massive amounts of heat. The cross-drilled holes and exotic materials are a testament to the violent energy conversion taking place with every hard stop. Developing a mechanical empathy for these components means understanding that every application of the brakes is a demand placed upon them. On public roads, this translates to braking earlier and more progressively than you think you need to, always keeping a massive reserve of stopping power for the unexpected.

Action Plan: Mastering High-Performance Braking

- Feel for feedback: Pay close attention to changes in pedal feel, which can indicate brake fluid heating or pad glazing. Your connection to the car’s mechanics is critical.

- Practice progressive pressure: In a safe, open area, practice applying braking pressure smoothly and progressively. Avoid sharp, sudden “stabbing” motions which can upset the car’s balance and lock a wheel.

- Monitor temperatures: If your car has brake temperature indicators, use them. Understand that cold brakes and tires require a significantly longer warm-up period and distance to reach optimal performance.

- Allow for cooling: On spirited drives through winding roads, consciously build in cooling periods between hard braking applications to prevent heat-induced brake fade.

- Learn the threshold: Practice threshold braking in a controlled environment (like an autocross event) to understand exactly where your car’s limit of grip is before the ABS engages.

How to Anticipate Other Drivers’ Errors Before They Happen?

Anticipation in a high-performance car is not a passive skill; it is an active, defensive strategy. You anticipate other drivers’ errors by using your car’s superior capabilities to create an abundance of two things: space and time. The common temptation is to use a powerful car’s acceleration to close gaps and assert presence. This is a novice mistake. A disciplined driver does the exact opposite, employing what professional racers refer to as “de-escalation driving.”

This strategy involves actively scanning the road two to three cars ahead, identifying traffic clusters, and recognizing potential conflicts before they materialize. You then use your vehicle’s potent acceleration and braking not to compete, but to strategically position yourself away from these clusters. Are two cars about to merge into the same space ahead? You don’t speed up to get there first; you ease off or make a decisive lane change to remove yourself from that equation entirely. You are using the car’s performance to *avoid* situations, not to win them.

The Professional Driver’s Approach to Road Safety

Professional racers like Graham Rahal and Andy Pilgrim emphasize a counterintuitive approach to street driving. They advocate for using a performance car’s superior abilities to create safety buffers. Instead of closing gaps, they use the powerful brakes to open up following distances instantly. Instead of aggressive acceleration, they use a quick burst of speed to move into an open lane, far away from a developing traffic jam or an erratic driver. Their entire focus is on “de-escalation”—using performance to place the car in the safest possible position on the road, constantly maintaining multiple escape routes should another driver make a mistake.

This requires a significant mental shift. You must view every other vehicle as a potential, unpredictable hazard. Your goal is to create a bubble of safety around your car at all times. This means maintaining a larger following distance than in a normal car, constantly checking mirrors, and positioning yourself in lanes that offer the most options to maneuver. You drive as if you are invisible to everyone else, because in a low, fast car, you very nearly are.

RWD vs. FWD: Which Handling Characteristics Are Safer for Novices?

The debate between Rear-Wheel Drive (RWD) and Front-Wheel Drive (FWD) is central to performance driving, and for a novice, the differences have critical safety implications. It comes down to how the car behaves at the limit of grip. A FWD car’s typical failure mode is understeer, where the front tires lose traction and the car pushes wide in a corner. An RWD car’s failure mode is oversteer, where the rear tires lose traction and the back of the car slides out.

For an inexperienced driver, understeer is generally more intuitive to correct. The natural human reaction—lifting off the throttle—is often the correct one, as it transfers weight to the front of the car, helping the tires regain grip. Correcting oversteer, however, requires a counterintuitive set of actions: counter-steering (turning into the slide) and delicate throttle application, skills that must be learned and practiced. While modern RWD cars are equipped with highly sophisticated multi-stage stability control systems that can mitigate this risk, the fundamental physics remain.

The following table breaks down the key differences and their safety implications for a driver who is still calibrating their skills to a performance vehicle.

| Characteristic | RWD (Rear-Wheel Drive) | FWD (Front-Wheel Drive) | Safety Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Failure Mode | Oversteer (tail slides out) | Understeer (pushes wide) | FWD more intuitive to correct |

| Electronic Aids | Advanced multi-stage stability control | Basic traction control | Modern RWD can be safer with electronics |

| Weight Distribution | More balanced (50/50 possible) | Front-heavy (60/40 typical) | RWD better for performance driving |

| Torque Steer | None | Significant in high-power models | RWD more predictable under acceleration |

| Wet Weather | Requires more skill | Generally more forgiving | FWD advantage in low-grip conditions |

Ultimately, a modern RWD car with its electronic safety nets engaged is exceptionally safe. However, a novice driver must understand that these systems are masking the car’s true nature. The danger arises when overconfidence leads to disabling these aids before the driver has developed the muscle memory to handle oversteer. For this reason, a high-power FWD vehicle can sometimes be a more forgiving, if less dynamically pure, entry into the world of performance driving.

The “Dunning-Kruger” Effect Behind Most Single-Car Accidents

The single most dangerous component in any high-performance vehicle is not the engine or the chassis; it is the driver’s own mind. Specifically, a cognitive bias known as the Dunning-Kruger effect, where individuals with low ability at a task tend to overestimate their own competence. In driving, this is a fatal flaw. The less skilled you are, the less aware you are of your own shortcomings in reaction time, judgment, and car control. This is backed by sobering data: AAA research reveals that while 90% of accidents are due to human error, 73% of drivers believe they are above average in skill.

High-performance cars act as a dangerous amplifier for this effect. During the first weeks of ownership, the car’s immense grip, powerful brakes, and sophisticated stability control create an illusion of mastery. The car feels so planted, so capable, that it masks the driver’s sloppy inputs and poor decisions. This breeds a false confidence. The driver starts to believe the car’s capabilities are their own. This is the “peak of Mount Stupid,” and it is where most single-vehicle accidents occur, typically within the first 3 to 6 months of owning a new performance car.

The critical incident happens when this unearned confidence leads the driver to push beyond their actual skill envelope—or worse, to disable the electronic safety systems that were creating the illusion of skill in the first place. When a genuine emergency occurs, the driver is suddenly confronted with the raw physics of the car and discovers, catastrophically, that they lack the calibrated skills to control it. The only antidote to this is a disciplined commitment to cognitive calibration: the humble, conscious process of seeking feedback, acknowledging your limits, and slowly and deliberately expanding your skills through professional instruction.

You must actively fight the urge to believe you have mastered the car. Assume you are not as good as you feel. Stay humble, keep the safety systems on, and focus on being smooth and deliberate, not fast.

Problem & Solution: Adjusting Coilovers for Daily Comfort vs. Track Days

Many performance cars come equipped with adjustable suspension, or “coilovers,” allowing the driver to fine-tune the car’s handling. The common mistake is assuming that a stiffer setting is always “better” or more “sporty.” This is a dangerous misunderstanding of suspension dynamics, especially on public roads. An overly stiff setup is not just uncomfortable; it is fundamentally unsafe for daily driving.

The problem is that public roads are imperfect. They have bumps, cracks, and undulations. A suspension that is too stiff will cause the car to become “skittish,” literally bouncing the tire off the pavement over these imperfections. For that brief moment the tire is airborne, you have zero grip and zero control. A good street setup must be compliant enough to allow the tire to maintain contact with the road surface at all times. Maximum grip comes from maximum tire contact, not maximum stiffness. This is a core tenet of mechanical empathy.

The solution is a disciplined, methodical approach to adjustment. Start with the manufacturer’s recommended “street” or “comfort” settings as your baseline. These have been engineered by experts for real-world conditions. For daily driving, you want damping set towards the softer end of the spectrum, typically around 30-40% from full soft. This ensures the suspension can absorb imperfections and keep the contact patch of the tire pressed firmly to the asphalt. For a track day, you can then increase the compression and rebound settings, but do so incrementally—only 3 or 4 “clicks” at a time from your proven street setting. A car that is predictable and inspires confidence will always be faster and safer than one that is overly stiff and nervous.

Keep detailed notes of your settings. Take a photo with your phone of the adjustment knobs for your “street” setup and your “track” setup. The goal is not to find the absolute stiffest setting, but the one that provides the most confidence and predictability for a given environment.

Why Hybrids Lose Their Efficiency Advantage at Speeds Over 70 MPH?

At first glance, the operating characteristics of a hybrid vehicle seem entirely unrelated to a high-performance sports car. Yet, they teach the same crucial lesson: every machine has an optimal operating window where it is both effective and predictable. A hybrid is most efficient at lower speeds where it can rely on its electric motor and regenerative braking. At sustained highway speeds above 70 mph, the gasoline engine is doing all the work, and the hybrid system becomes dead weight, losing its efficiency advantage.

This concept of an “operating window” is directly applicable to your performance car, particularly if it has a turbocharged engine. Turbocharged engines do not deliver power linearly. They have a specific RPM range, or “powerband,” where they produce maximum torque and horsepower. Below this range, the engine can feel sluggish (turbo lag). When the turbo spools up and the engine enters the powerband, the car can experience a sudden, sometimes violent, surge of power. This transition can be a major factor in losing control.

Understanding this is a vital part of mechanical empathy. Being in the wrong gear at the wrong RPM in a corner can be disastrous. For example, entering a turn with the RPMs too low and then applying throttle could cause a delayed but massive power surge mid-corner, instantly overwhelming the rear tires and causing oversteer. A disciplined driver learns their engine’s specific powerband and ensures they are always in the correct gear to keep the engine in its most predictable and responsive range. You learn to avoid the sudden transitions that can upset the car’s balance.

Just as the hybrid driver must respect the car’s designed speed limits for efficiency, the performance driver must respect the engine’s RPM limits for predictable power delivery and safety.

Why a 5-Star Rating Doesn’t Always Save You in a Collision With a Truck?

Your sports car’s 5-star safety rating is a source of comfort, but it comes with a critical asterisk that every performance car owner must understand. These ratings are determined by crash tests conducted against barriers or vehicles of a similar mass. They tell you how well your car will protect you in a collision with another car. They tell you almost nothing about what will happen in a collision with a fully-loaded commercial truck.

The physics are brutal and simple: it’s a battle of mass, and you will lose. As physics calculations demonstrate, commercial trucks can weigh 10 to 20 times more than performance cars. In a collision, your car’s advanced crumple zones, airbags, and safety cage will be overwhelmed by the sheer kinetic energy of the truck. Your 5-star car effectively becomes the truck’s crumple zone. There is no engineering solution that can reliably protect a 3,500-pound car from a 70,000-pound truck.

The only solution is absolute, total avoidance. This requires a heightened state of situational awareness specific to driving a small, low-profile vehicle among giants. You must operate under the assumption that you are completely invisible to truck drivers. Their blind spots are enormous, and your car can easily disappear within them. Therefore, you must adopt a strict set of rules:

- Never linger beside a truck. Either stay far behind it or pass it decisively and quickly. The side of a truck is a death zone.

- Maintain extra following distance. This gives you more time to react if the truck brakes suddenly or has a tire blowout.

- Position yourself to see their mirrors. A good rule of thumb is that if you cannot see the driver in their mirror, they absolutely cannot see you.

- Use your acceleration for safety. Your car’s performance advantage should be used to create space and escape these dangerous positions, not to challenge a vehicle that outweighs you by a factor of 20.

Your safety rating is for a world of cars. On a highway filled with trucks, your only true safety feature is your own discipline and awareness.

Key Takeaways

- Physics are absolute: Doubling your speed quadruples the kinetic energy your brakes must dissipate. Energy management is your primary job as a driver.

- Your mind is the biggest risk: Driver overconfidence, amplified by a car’s high grip, is a leading cause of single-vehicle accidents. Cognitive calibration is mandatory.

- Maintenance is safety: High-performance consumables like tires and brake fluid are non-negotiable safety equipment, not optional expenses. Compromising on them is reckless.

What Are the Hidden Costs of Owning a Sport Coupé as a Daily Driver?

The true cost of performance car ownership is not the sticker price; it is the unwavering and non-negotiable commitment to its maintenance. Treating the upkeep of a performance car like that of a standard commuter vehicle is not just neglect—it is an act that directly compromises its safety and engineering integrity. This is the final and perhaps most important test of a driver’s discipline.

High-performance cars achieve their incredible grip and stopping power by using components made from softer, more aggressive compounds that wear out much faster. These are not optional upgrades; they are the very foundation of the car’s designed safety envelope. As performance driving instructor Eduardo de Sousa states, this commitment is absolute.

The highest cost is not the price tag, but the non-negotiable commitment to using high-performance consumables. Putting cheap, all-season tires on a Porsche 911 is not a ‘saving’, but a reckless act that completely compromises its engineering and safety.

– Eduardo de Sousa, ES Supercar Training Professional Assessment

This principle of mechanical empathy extends to your wallet. You must budget for these accelerated replacement cycles. A performance summer tire may only last 10,000 miles, compared to 40,000 for a standard all-season. Brake pads and rotors, which bear the brunt of managing the car’s immense kinetic energy, will also require far more frequent—and expensive—replacement. The table below, based on an analysis of real-world ownership data, illustrates the stark reality.

| Component | Standard Car Interval/Cost | Performance Car Interval/Cost | Safety Impact if Neglected |

|---|---|---|---|

| Summer Performance Tires | 40,000 miles / $600 | 10,000 miles / $1,600+ | Critical – Loss of designed grip levels |

| Brake Fluid | 2 years / $100 | Annual / $200 | High – Brake fade risk |

| Brake Pads/Rotors | 50,000 miles / $500 | 15,000 miles / $2,000+ | Critical – Reduced stopping power |

| Suspension Components | 80,000 miles / $800 | 30,000 miles / $3,000+ | Moderate – Handling degradation |

Ignoring these costs is not saving money; it is systematically dismantling the very systems designed to keep you safe. The true cost of daily driving a performance car is accepting this financial reality as a non-negotiable part of the ownership experience.

To put these principles into practice, the next logical step is to seek out qualified, professional instruction. A high-performance driving education (HPDE) event or a one-on-one session with a certified instructor is not an expense; it is the most critical investment you can make in your own safety and enjoyment of the car.